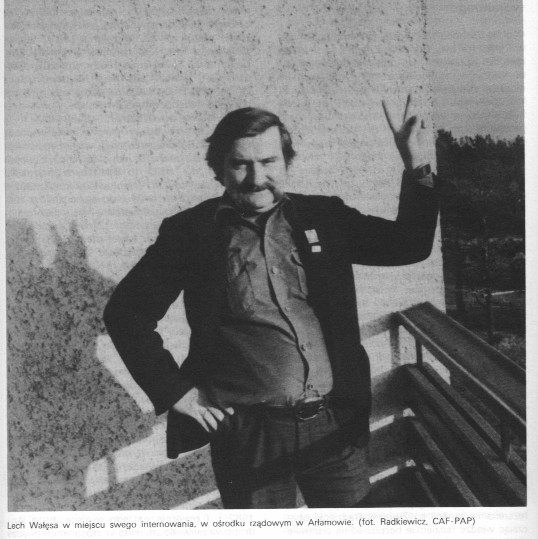

An interned Lech Walesa showing Solidarity V for victory sign: [Miroslawa Marody, Dlugi Final (The Long Final), Warsaw, 1995].

| Anna M. Cienciala (hanka@ku.edu) | History 557 Lecture Notes |

Spring 2002 (Revised Dec. 2003) |

The Path toward 1989, and the Collapse of Communism in E. Europe

A. Toward Collapse, 1982-88.

Preface

The collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe was not unexpected by specialists in the region, though its suddenness and speed came as a great surprise them. Of course, the roots of the 1989 revolutions can be seen as beginning with the unrest/revolts that took place in East Germany in 1953, Poland and Hungary in 1956, followed by Czechoslovakia in 1968, then workers’ revolts in Poland in 1970 and 1976, the dissident movements in Poland and the Solidarity period in 1980-81.

However, what is often neglected, is the period between the crushing of Solidarity in December 1981 and the revolutions of 1989, yet it was in these years that similar kinds of peaceful opposition, with similar goals of peaceful democratization and reform, developed in Poland and Hungary. They were accompanied by smaller movements in Czechoslovakia and East Germany, while brave individuals risked their lives to protest the system in the Balkans, especially in Romania.

Equally important was the political liberalization pursued by Mikhail S. Gorbachev in the USSR, which encouraged reform communists and - though unintentionally - dissident movements in Eastern Europe, especially Poland and Hungary. In fact, Gorbachev and the reform communists in those countries supported a gradual, controlled liberalization which would preserve communism. They did not expect the collapse of communist regimes that took place all over Eastern Europe in 1989.

1. Poland 1982-1988: Underground Solidarity and Civic Society, Economic Crisis, and the Gorbachev Factor.

General Jaruzelski allowed the Polish legislature to lift Martial Law in July 1983, and the "interned" leaders were gradually released - though some were re-arrested later.

An interned Lech Walesa showing Solidarity V for victory sign: [Miroslawa Marody, Dlugi Final (The Long Final), Warsaw, 1995].

A few Solidarity leaders who managed to avoid arrest, stayed underground..They carried on press, radio, and sometimes even TV action against the government by breaking into the government radio and TV network. At the same time, an extensive underground Civic Society developed in Poland in the years 1982-89. Its members, who were mostly intellectuals, were organized in various groups, held underground seminars, staged plays, poetry readings, art exhibits, and above all, published newspapers, periodicals, and books.

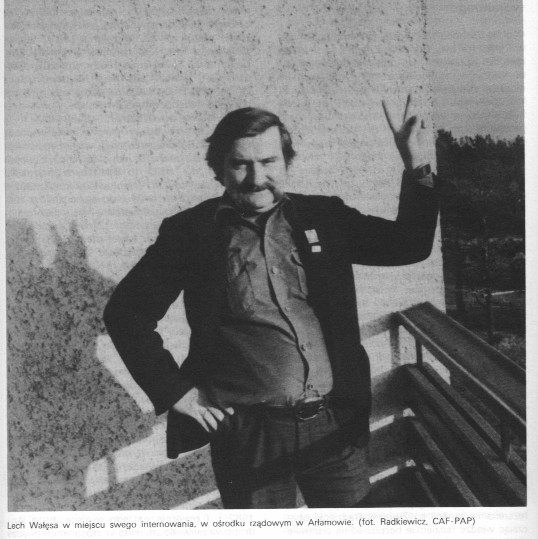

Underground literature book covers, 1981,1983

[from: Marody,Dlugi Final].

In this way, democratic ideas were developed, also ideas on the establishment of a free market economy - although Solidarity leaders assumed the Welfare State would exist alongside it. (This proved an illusion). Individual dissidents were often harassed.

The underground organized mass demonstrations on key anniversaries

in Polish history: May 3 -the anniversary of the May 3 1791 Constitution -also

November 11- the prewar independence day. In most cases, these demonstrations

were dispersed by riot police using clubs and water cannon.

|

|

| Official may 1 demonstration,1982 | Solidarity counter-demonstration |

[From: Miroslawa Marody, Dlugi Final].

[Bibliography:

On the Polish underground society of the 1980s, see: (1) Stanislaw Baranczak, Breathing under Water and other East European Essays, (Cambridge, Mass, & London, England, 1990) - a study of Polish intellectual and literary life by a poet and translator, holder of the Alfred Jurzykowski Chair in Polish Language and Culture, Harvard University. (2) Maciej Lopinski, Marcin Moskit, Mariusz Wilk, KONSPIRA. Solidarity Underground, translated by Jane Cave, Afterword by Lawrence Weschler, (Berkeley, CA.,1990) - by three journalists, members of Solidarity. See also: (3) Michael T. Kaufman, Mad Dreams, Saving Graces. Poland: A Nation in Conspiracy, (New York, 1989) - An American journalist, son of a Polish-Jewish communist, writes of his experiences in Poland, 1984-87. (4) Adam Michnik, Letters from Prison and Other Essays, translated by Maya Latynski, (Berkeley, CA., 1985) - fascinating letters and essays by one of KOR’s leaders, later in Solidarity, and since spring 1989 editor of a leading Polish newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza and important political player in 1989; see also (5) essays by Ewa Kuryluk and Adam Michnik in: William M. Brinton and Alan Rinzler, eds., Without Force or Lies. Voices from the Revolution in Central Europe in 1989-90, (San Francisco, CA.1990), pp. 211-222, 239-252; (6) Andrew Nagorski, The Birth of Freedom. Shaping Lives and Societies in New Eastern Europe, (New York, 1993) - by a Polish-American journalist, Chief of Newsweek’s Warsaw bureau, 1980s, who had contact with Polish, Czech and Hungarian dissidents. (7) Janine Wedel, The Private Poland, (New York, 1986) - an American Anthropologist writes of life in Poland as seen in visits and interviews between 1977 and 1986. This is an excellent view of Polish life in those years].

Of course, the vast majority of the Polish population did not belong to underground organizations; they retreated into private life and tried to limit their interaction with state institutions as much as they could.

Continuing price increases forced many people to go without. Many turned to gardening on small plots to provide vegetables and fruit, while the more enterprising thrived in the "Second Economy," that is, the Black Market. Gen. Jaruzelski and his administrations tried to reform the economy. Taking a cue from Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s "perestroika" (reconstruction), in October 1987, the P. government went further than the USSR. It announced extensive economic reforms, especially a price increase, even though a 450% increase had taken place in January 1982 and others after it. This time, a referendum was held in November 1987, which showed that the 60% of the electorate who voted preferred a gradual to a one time increase.

In the same referendum, people were asked whether they supported a "Polish Model" for democratizing political life, that is, strengthening self-government, extending the rights of citizens, and increasing their participation in political life. Two fifths of the respondents supported the "government program" - which, in fact, had been outlined by Solidarity in 1981. At the same time, unofficial opinion polls showed that only about 25% of the population supported the regime. It is not surprising that General Jaruzelski’s "Patriotic Movement of National Rebirth," (Patriotyczny Ruch Odrodzenia Narodowego, PRON), created in July 1982, did not enjoy much support, though it included some respected public figures.

As prices continued to rise and goods became ever more scarce, social services deteriorated and the standard of living continued to fall, so criticism of the government increased. Meanwhile, the government’s economic "reforms" were largely bureaucratic. They consisted of reducing the number of ministries by combining them, also theoretically allowing state enterprises more freedom in production plans and use of foreign currency earned; making enterprises self-financing; reducing central planning, and making efforts to extend self-management by workers.

All these points, along with one other - open discussion of economic questions by various institutions including parliament - were listed in the "Reformed Economic System" worked out by Solidarity economic advisers in 1981, but the government had rejected most of them as unfeasible in 1982.*

*[For the Solidarity experts’ proposed "Reformed Economic System" see: J.F.Brown, Surge to Freedom. The End of Communist Rule in Eastern Europe, (Durham and London), 1991, p.82].

However, when adopted half-heartedly after 1985 - except

for free discussion - these reforms did not work and amounted only to tinkering

with economic problems, which was also true to Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s

economic "reforms" in the USSR. The main problem was always the same - the party’s

fear that economic liberalization would led to loss of control over the economy

and thus the rise of an economically independent opposition.

Meanwhile, the underground Civic Society, made up mostly of writers, actors, artists, and other intellectuals, became ever more active, and the underground printing of newspapers and books kept on increasing. How could the Poles develop such widespread resistance, and why did the authorities more or less tolerate it after 1985? Seven interrelated factors can be cited for this state of affairs, listed here in their order of importance as perceived by the author of this text:

(1) Solidarity’s ability to establish an underground network. This owed much to the Polish tradition of underground resistance, going back to the 19th century, honed under the German occupation in World War II, now bolstered by smuggled printing presses and paper largely paid for by the U.S. labor organization IFL-CIO - whose leader, Lane Kirkland (died 1999), was an ardent supporter of Solidarity - and to some extent by contributions from the CIA. However, the Solidarity underground movement and the Civic Society would not have been successful without:

(2) Papal and church support for (a) for the underground Civic Society, (b) the restoration of Solidarity ;

(3) outstanding intellectual advisers to Solidarity leaders (though they became more important in 1988);

(4) the continuing economic crisis and deteriorating standard of living which destroyed any remaining popular confidence in the government-party leadership;

(5) Lech Walesa’s prestige, though he was not seen publicly between 1983, when he was released and received the Nobel Peace Prize (his wife received it for him in Oslo), and the TV debate in December 1988;

(6) the liberalizing policies of Mikhail S.Gorbachev elected by the Central Committee as lst Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in March 1985;

(7) "Reform Communists" within the Polish party leadership who enjoyed Gorbachev’s support. Indeed, Gorbachev and the Polish Reform Communists were key to the liberalization that took place in1985-88, and they played a crucial role in the collapse of 1989 - although ironically, neither party leadership expected this collapse to take place.

Here it is worth citing a remarkable forecast about Gorbachev made by Adam Michnik a KOR-Solidarity leader - trained as a historian - in a letter written from Gdansk prison in early 1985:

The Soviet state has a new leader; he is a symbol of transition from one generation to the next within the Soviet elite. This change may offer an opportunity, since Mikhail Gorbachev has not yet become a prisoner of his own decisions. No one can rule out the possibility that an impulse for reform will spring from the top of the hierarchy of power. This is exactly what happened in the time of Alexander II and, a hundred years later, under Khrushchev. Reform is always possible, even in the face of resistance by the old apparatus. Leaders of the Kremlin may wish to take on the challenge of modernity; they may begin searching for a new model of relations with Soviet satellites. Polish political thought must be prepared for this contingency. Phobias and anti-Russian emotions provide no substitute.*

Gorbachev.

Who was this new Soviet leader and what did he want to

accomplish? Mikhail Gorbachev was a relatively young member of the Soviet

party elite (b.1931), so he was 54 when he became General Secretary of the Soviet

Party in March 1985. Also, he had been greatly influenced by Khrushchev’s

1956 and 1961 revelations of the evils of Stalinism.

He set out to reform the Soviet economy to make it more productive and catch

up technologically with the West, especially the United States. He realized

these aims could not be achieved without ending the Cold War, and thus the arms

race with the U.S. He was particularly worried by the American Strategic

Defense Initiative ( SDI or Star Wars) which, if successfully developed,

would produce missiles to shoot down Soviet missiles in space, thus undercutting

and perhaps even nullifying Soviet nuclear capabilities. (Such U.S. missiles

have not been developed as yet!) He therefore bent all his efforts toward peace

and signed a series of important agreements with President Ronald Reagan.

(President 1980-88). They included arms limitation and cultural agreements,

as well as the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan.*

*[Russian forces left Afghanistan in February 1989, but the USSR continued to supply and support the new Communist leader there, Mohammed Najibullah until he resigned in April 1992 and was succeeded by a new Afghani government led by Burhanuddin Rabbani. Najibullah found refuge in the U.N. Legation in Kabul, but was murdered with his brother by the fundamentalist Islamic Taliban when they took the city in fall 1996. After the terrorist attack on the WTC towers in New York, Sept. 11, 2001, the U.S. government sent armed forces to attack and defeat the Taliban in Afghanistan,. Tne Taliban were subsidized by Osama Bin Ladin, who organized the WTC and previous attacks on U.S. agencies abroad. His followers ran training camps for terrorists in Afghanistan. The Taliban were defeated by U.S. and other NATO forces, but Bin Ladin's fate is unknown and the Al-Queida is still active].

Gorbachev met with stiff resistance to his economic reform plans from hardliners in the Soviet leadership. Therefore, he launched the slogan of "Glasnost," or open discussion. This really meant open discussion of the past, especially the evils of Stalinism, but its major goal was political - to discredit Gorbachev’s critics, most of whom believed that Stalin was a great Soviet leader and opposed reform.

Gorbachev’s Glasnost policy led not only to open discussion in the Soviet media, but also to increasing liberalization of the media in Poland and Hungary in the years 1985-88. In those two countries, controlled political liberalization was supported by "Reform Communists." Indeed, in Poland, one of their leaders, Mieczyslaw F. Rakowski (b.1926), wrote in a confidential memo of October 1987, which was leaked to the press: "In practice, we have already recognized the opposition as a lasting element on the country’s political map."*

*[cited in: Timothy Garton Ash, "The Opposition," New York Review of Books, October 13, 1988, p. 4, note 9).

Communist Liberalization in Poland.

Examples of the government’s liberalization included a relatively lenient policy toward the underground (although a few of its less known members were murdered while well known members were harassed). Furthermore, the government allowed meetings between U.S. diplomats and Polish opposition leaders, notably Lech Walesa. In fact, Vice-President George H.W. Bush met with him when he visited Poland in 1987, as did the Pope, who was also allowed to see him, though not in Gdansk The Pope’s third visit in June of that year, lifted people’s spirits. (He had come for the second time in June 1983, when he pushed for amnesty for political prisoners, granted in July, and for the re-legalization of Solidarity). Now, he made these demands again. At the same time, foreign dignitaries including Bush began pay their respects at the grave of Father Jerzy Popieluszko (1947-1984), a popular Warsaw preacher who conducted special monthly "Fatherland Masses" attended by people from all over Poland, supported Solidarity. Popieluszko was murdered by Polish security police in October 1984. His death provoked such outrage that the government was forced to mount a public trial in which three policemen directly involved were condemned to prison. (We still don't know if there was an order to kill Popieluszko,or if he was killed accidentally when struggling with one the policeman who kidnapped him, In any case, one of the policemen admitted to killing him and got the longest prison sentence).

Thus, the liberalization of life in Poland after 1985, was the result of many factors, but especially: Gorbachev’s policy of Glasnost, its support by Polish Reform Communists and his support of them; church support of Solidarity and the civic society; the continuing economic crisis, and the government’s desire to have the U. S. Government lift the economic sanctions imposed by President Reagan as punishment for Jaruzelski’s martial law. (They were gradually lifted as the Polish government relaxed restrictions).

Economic Crisis and Worker Unrest.

However, as the 1980s drew to a close, the endemic economic crisis was made even worse by Poland’s huge foreign debt. In 1970, it had amounted to $1 billion, but in 1989 it stood at $38 billion, most of it owed to West Germany and the United States. Therefore, the Polish government exported as much as it could, thereby making consumer goods, especially meat products, more scare and expensive than before. Even so, the money earned by the exports could not even cover the yearly interest on the debt.

At the same time, the price of Soviet oil had gone up six-fold since 1970 and in the late 1980s the USSR began to demand payment in dollars. It is true that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) rescheduled the Polish foreign debt, but this did not make the domestic situation any easier. As prices continued to climb and scarcity continued, public opinion polls showed that people were growing ever more critical of the government, which was blamed for beggaring the nation. It was also blamed for not responding adequately to the fall out from the April 1986 Chernobyl nuclear plant explosion in Ukraine, which affected north-eastern Poland.

The economic situation finally sparked new worker unrest. There were two waves of workers’ strikes, in May and August 1988, in which young workers - children in 1980-81 - demanded the re-legalization of Solidarity. This was also the demand of the Pope and the U.S. government since Dec. 1981.

In late August and mid-September, there were talks between representatives of the government and the opposition with the participation of high churchmen, but they did not yield immediate results because the two sides were still too far apart. Also, there were conflicts between hardliners and reform communists in the party leadership.

Walesa re-emerges, end November 1988.

The Polish government made a great mistake by allowing a TV debate on November 30, between Lech Walesa and the leader of the government-controlled trade union, Alfred Miodowicz. The government assumed that the latter, an experienced politician and a good debater, would win in a studio setting, where Walesa would not have a crowd responding to him. However, Walesa - after brief coaching by film directors and others - won hands down and his victory was seen on TV by some 20 million Poles, many of whom saw him for the first time.

Walesa was then allowed to go to Paris in early December,

for the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights (pushed through by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1948). He

was received in France like a head of state.

At home, his supporters organized a Civic Club to prepare for

political action.

Divisions in the Polish party leadership.

As mentioned earlier, there were divisions within the leadership. It is known that heated debates over policy took place at the Party’s Central Committee Plenum meetings on December 20-21, 1988, and January 16-17, 1989. In the first round, Premier Mieczyslaw Rakowski declared his support for an attempt to reach a general understanding with the "constructive opposition" (presumably those viewed as moderates). He asked whether, in view of the bad economic situation, the party leadership should or should not allow the re-legalization of Solidarity. The party members attending were to answer in the second round of the Plenum in January.

On January 16-17, the "reform communists" led by the General Jaruzelski, Premier M. Rakowski, Interior Minister General Czeslaw Kiszczak, and Defense Minister General Florian Siwicki, faced a massive attack by the hardliners, who probably enjoyed the support of Soviet hardliners, opponents of Gorbachev. However, when the reformers threatened to resign and generals supported Jaruzelski, the opposition retreated. The Plenum cast a vote of confidence in the Politburo and approved a draft resolution on the Central Committee’s stand regarding political and trade union pluralism. One may assume that the resignation of the leadership was unthinkable due to the support they enjoyed from the Soviet President, Mikhail S. Gorbachev. In any event, the way was now open to talks between the government and the opposition.*

*[For the "Roundtable Talks," see Poland in Lec.Notes 19B below]..

2. Hungary, 1981-1988.

Gorbachev sanctioned political liberalization in this country as well, but here too there were disagreements within the Party leadership on what policy to follow.

Debates and changes in Hungarian Party leadership.

One of the "reform communists" in the Hungarian Socialist

Workers’ Party (HSWP) Imre Pozsgay, talked of restoring political

pluralism, though he meant the participation of some opposition parties

in a government still dominated by Communists. In April 1988, he proposed a

"reform program" with himself as the leader of a "reformed" party. However,

his program was watered down at party meetings, and Kadar’s proposal

to replace one third of the Central Committee and approve his (Kadar’s) candidacy

for continued leadership was rejected in May.

Kadar agreed to resign in return for a guarantee that (a) he would not

be made the scapegoat for Laszlo Rajk’s execution 1949, (b) he would

not be prosecuted for his role in the 1956 revolution, the subsequent persecution

and death of its participants, especially Imre Nagy and associates, and

finally (c) that he would not be held responsible for the unsuccessful economic

reforms of the 1970s.

With Moscow approval, Karoly Grosz now emerged as both party leader and Prime Minister. He and his supporters rejected Pozsgay’s "democracy package plan." It called for far reaching constitutional and legal reforms, including freedom of assembly, press, trade unions, minority rights, human rights, plebiscites, local self-government, and a new constitution. Poszgay, a Politburo member who controlled the media, was at this time the most popular party leader. In June, K. Grosz lost out as party leader to a collective HSWP Presidium of three reformers: Miklos Nemeth, Rezso Nyers, I. Pozsgay plus Grosz, the conservative. This collective leadership lasted until the party congress on November 9, 1988

Economic Crisis.

Meanwhile, the economic situation had

been deteriorating from the mid-1980s. Much as in Poland, this was due to

a combination of factors: the drastic increase in the price of Soviet oil between

1970 and 1989, also Soviet demands that it be paid with dollars; a huge foreign

debt, and most of all, inflation.

At the same time, there was a growing gap between the rich and the poor, and

older people were unable to live on their fixed pensions. These factors led

to increased rates of divorce, alcoholism, and suicide, the latter being particularly

noticeable.

The economic crisis strengthened the opposition groups - as did unestricted travel to neighboring Austria. This prosperous country became the yardstick for judging the Hungarian party-government leadership, showing up its failures.

Finally, the authorities were also blamed for not standing up for the Hungarian minority in Romania (Transylvania), which was being viciously persecuted by the Romanian dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu.

Dissidents.

It should be noted that by the end of 1988, there were 22 political groups in Hungary, whose names included the words: society, league, association, or front. There were also resuscitated embryos of two old parties:"The Independent Smallholders’ Party" and the "Socialist Party."

However, it was the Hungarian dissidents who were the most visible from 1985 onward. In mid-October 1985, the Hungarian authorities organized a "European Cultural Forum" in the swank Intercontinental Hotel, Budapest. At the same time, Hungarian dissidents grouped in the "International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights," organized a parallel, unofficial forum of their own. They invited western writers including Susan Sontag from the U.S., Magnus Enzensberger from West Germany, and some E. European writers living in the West, to a conference, also in the Intercontinental Hotel, to discuss topics such as: "Writers and their Integrity," and "The Future of European Culture." When the authorities refused to let them have a conference room in the hotel, the symposium adjourned to a private apartment - belonging to a writer who supported censorship but happened to be in West Berlin. A good time was had by all. *

*[see: Timothy Garton Ash, "A Hungarian Lesson," first published in the New York Review of Books, Dec. 5, 1985, reprinted later in his book: The Uses of Adversity. Essays on the Fate of Eastern Europe, (New York,1989), pp.143-156; also: Gale Stokes, ed., From Stalinism to Communism. A Documentary History of Eastern Europe since 1945, 2nd edition, (Oxford, 1996), pp. 232-241, also essays by Tomas Aczel and George Paul Csicsery in: Without Force or Lies, pp.283-304.]

By the end of 1988, the political situation in Hungary was in a state of ferment.

3. Czechoslovakia 1981-1988

As in Poland, so too in Czechoslovakia there was an steady growth of "Samizdat" - the Russian word for self-publishing without government permission. However, unlike Poland (where printing presses were used) but like the USSR, these "publications" were produced on typewriters. Each recipient would make several carbon copies and pass them on, so this activity involved a very small number of people.*

*[see: H. Gordon Skilling, Samizdat and an Independent Society in Central and Eastern Europe, (Columbus, Ohio, 1999). This is an excellent overview of independent publications in the USSR, Central and S.E.Europe. On Czech Samizdat, see: Marketa Goetz-Stankiewicz, ed., Twenty Years of Czechoslovak Underground Writing, (Evanston, IL., 1992), this adds more detail to that given by Skilling. See also essays by Josef Skovercky and Vaclav Havel in: Without Force or Lies, pp. 253-283].

However, most of the Czech and Slovak population was not interested in dissent. There were three main reasons for this state of affairs: (1) The Czechs had a tradition of cooperating with authorities; (2) the Slovaks had more autonomy since the Prague Spring of 1968, and (3) the economic situation in the country was much better than in Poland. As one dissident writer, Vladimir Kusin, put it, Gustav Husak - who was party leader since January 1969 - had a successful policy consisting of the three Cs: "coercion, circuses, and consumerism." Indeed, the Czechs had more cars per head than other satellite countries, except East Germany, and more sausage and beer than the East Germans. Also, many professional people had small country cottages, where they could retreat on weekends and for summer holidays. All could also enjoy good entertainment, including music - even jazz, though it was frowned on and finally repressed by the authorities.

There was negative economic growth in 1981-82, but the government’s "intensification" reforms, mainly cutbacks and savings, led to an upswing in 1983-85, and the foreign debt was very small. In 1986, reforms in agriculture reduced obligatory deliveries by collective farms to grain and slaughtered animals. At the same time, there was a reduction in price subsidies for agricultural goods in order to use the savings for subsidizing the prices of high-quality products. In general, the average Czech or Slovak was not discontented with life until late 1989, and this meant little support for dissident movements.

Still, it should be noted that religious dissent

had appeared in the mid-1980s. On the 1,100th anniversary of the

death of St.Methodius in 1985,*150,000 Czechs and Slovaks engaged in

a peaceful demonstration. This heralded pressure to rectify injustices

to the R.C. church and demands for its independence from the state, also for

the appointment of more bishops.

A retired railway worker, Augustin Navratil, who had agitated for religious

freedom in the past and had been incarcerated in a mental hospital, now collected

thousands of signatures for the appointment of more Catholic bishops. The government

made three more appointments, but Navratil was committed again to a mental

hospital.

*[For a long time, Cyril and Methodius were credited with bringing Christianity to Bohemia from Constantinople, but scholars now believe it came from Rome].

Czechoslovak leaders reject reforms.

Unlike Poland and Hungary, but like East Germany, the Czechoslovak communist leaders rejected Gorbachev’s policies of Glasnost and proposals for economic reconstruction (Perestroika). Indeed, Vasil Bilak (one of the hardliners who had invited the Soviet leaders to launch an invasion of his country in 1968, and had always supported copying the Soviet model), now opted for "a national path" as distinct from the new Soviet path. Therefore, he and his colleagues opposed even gradual political liberalization along the lines of Gorbachev’s Glasnost, for fear this would lead to the breakdown of the system and the loss of their privileged position in another "Prague Spring."

Gorbachev did not insist, and when he visited Czechoslovakia in 1987, he did not openly condemn the Warsaw Pact invasion - which would have discredited the Czechoslovak party leadership.

Pressure for reform from outside the party.

However, social pressure for political relaxation and reform became evident in 1988. In August that year, many Czechs demonstrated - for the first time since 1969 - in memory of the 20th anniversary of the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968. They were put down by the police.

In November 1988, Czech dissidents led by Vaclav Havel tried to hold an international symposium to discuss the importance for Czechoslovakia of the years 1918, 1938, 1968, 1948, and 1968. The British expert onf E.Europe, historian Timothy Garton Ash was asked to attend, but the authorities canceled the symposium. *

*[See Garton Ash, "The Prague Advertisement," New York Review of Books, Dec. 22, 1988, and same author, The Uses of Adversity, pp. 228-241].

Thus, the Czech leadership remained deaf to Gorbachev’s hints at reform. When he visited the country in summer 1988, his spokesman, Gennadi Gerasimov was asked what was the difference between Gorbachev’s reforms in USSR and those in Czechoslovakia in 1988; Gerasimov answered: "Twenty Years," thus acknowledging that Gorbachev saw a reform model for the USSR in the Prague Spring of 1968.

In December 1988, Moscow officially condemned the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968, but in January 1989 a demonstration led by Vaclav Havel in memory of Jan Opletal - who had immolated himself twenty years earlier in protest against the invasion - was put down by the police. So, Czechoslovakia remained "frozen" until the late fall of 1989. This was largely due to the fear of the Czechoslovak leadership that any reform or relaxation would lead to their overthrow. *

*[ On Czechoslovakia, see J.F. Brown, Surge to Freedom,

ch. 6; for a detailed account,see: Bernard Wheaton & Zdenek Kavan, The

Velvet Revolution. Czechoslovakia, 1988-1991, Boulder, CO., 1992, Part One].

4. East Germany - the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

East German leaders also feared liberalization; not because they had weathered anything like the "Prague Spring" or the 16 month "Solidarity" era in Poland (1980-81), but because they felt threatened by the freedom and prosperity of West Germany - which could be seen by the East Germans on their TV sets.

The GDR has been aptly described as "the state without a nation." It was part of the German nation, which had been divided into eastern and western occupation zones by the victorious allies of World War II, who then entered the Cold War against each other and created two German states. The Germans were even more drastically separated in August 1961 by the Berlin Wall, erected to stem the mass flight of East Germans to West Berlin, and thence to West Germany.

The GDR was a police state in which the "STASI" - name for security police - penetrated society more than in any other Soviet style state except for the old, Stalinist USSR. But the main penetration, was of a different sort; it was increased travel between the two Germanies in the 1980s, and above all West German TV, which the communist authorities allowed East Germans to watch freely in the 1980s in the belief that their people were fully satisfied with their lives. This was, of course, patently untrue for the East Germans constantly compared their standard of living with the much higher one in West Germany (which even subsidized the GDR with special trade preferences). Indeed, by 1989, the German Federal Republic was subsidizing the GDR at the rate of 6-7 billion Deutschmarks per year as part of its policy of developing better relations between the two German states. The Soviet Union was giving subsidies of roughly the same amount, but the East German economy was still a deficit operation *.

*[see:"How East Germany Came to the Brink of Ruin," in: Legters, Eastern Europe, pp. 408-411]

Still, open expressions of discontent were rare. East German writers were allowed a brief interlude of freedom in 1972-1976. However, in November 1976, the ballad writer Wolf Biermann was deprived of his citizenship while traveling in Western Europe. Twelve leading East German writers wrote a letter of protest to the government and a hundred more signed it. The regime punished all the signatories in various ways, but especially by a publication ban. The writers responded in one of two ways: by an "inward emigration," or by an outward emigration to the West.*

*[For a leading East German writer, see examples of work by Reiner Kunze in: Without Force or Lies, pp. 145-169].

The Evangelical [Lutheran] Church and Dissent.

This state of affairs began to change after the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s birth in 1983. From this time onward, the outwardly loyal Evangelical (Lutheran) Church was given more freedom. It used this freedom to oppose certain aspects of GDR life. Thus, it opposed increased militarization, supporting the right to conscientious objection and alternative service. It welcomed Gorbachev‘s policy of open discussion, while the East German authorities opposed it.

In the late 1980s, small groups of dissidents met in church buildings to discuss their ideas for a reformed, liberalized, but socialist East German state. The first manifesto of the "Democratic Opposition" was drawn up by 21 leading Communist activists and addressed to the 11th Congress of the Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei, SED, the ruling communists) in April 1986. It contained strong criticism of the economic, ecological, educational and political situation. and a plea for real, as opposed to propaganda, work for peace by demilitarizing the GDR. In 1988, the chief dissident organization was "The New Forum," which demanded justice, democracy, freedom, and ecological safeguards. The NFR did not want a unification of Germany, but a democratic, socialist GDR.

The East German communist party, S.E.D (Socialist Unity Party)

led by Erich Honecker (1912-1994, in power from 1972 to late 1989), rejected

Gorbachev’s policies of Glasnost and Perestroika, because open

discussion and the free market threatened the very existence of the GDR.

Indeed, Soviet newspapers could not be sold in East Germany. (The same was true

of Cuba at this time).

Gorbachev tolerated this situation, but advised reform - advice that

he was to give openly on the 40th anniversary of the GDR’s founding,

October 6, 1989. It was, indeed, high time, for thousands of Germans were emigrating

to West Germany via Hungary.

[NOTE: for the background to the collapse of communism in the Balkan States see Lec. Notes 19 B below].

----------------------------------------

19B. 1989. The Collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe.

Preface

It is worth noting that this sudden collapse came as a surprise not only to Gorbachev and East European communists, but also to western public opinion, including most western experts on the Soviet bloc. It is true that Zbigniew Brzezinski , the Polish-born political scientist who was Security Adviser to President Jimmy Carter (1976-1980), predicted the collapse of the communist system in the USSR and Eastern Europe, but he did not foresee it happening so fast. Another western specialist, Antony Polonsky, at that time a historian of Poland in Britain, was shown in an ABC documentary in summer 1989 speaking on the collapse of communism (Program broadcast in December 1989). He expected the transition from communism to democracy in East Central Europe to take at least five years. *

*[Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Failure. The Birth and Death of Communism in the Twentieth Century, New York, 1989; the book was finished in August 1988. The 1989ABC documentary on the Fall of Communism was anchored by Peter Jennings; Polonsky now has the Chair of Judaic Studies at Brandeis University].

I. Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany.

1. Poland.

In January 1989, the Polish authorities proposed the re-legalization of Solidarity if Walesa guaranteed there would be no strikes in Poland for two years, but he refused. Then the authorities proposed negotiations with the aim of co-opting the opposition, but the latter rejected this. Therefore, the two sides agreed to hold negotiations in Roundtable Talks which lasted from Feb. 9 to April 6, 1989, and, after the government-party side failed once again to obtain the opposition’s agreement to be co-opted into a new government, the talks resulted in a series of important agreements. The main points of the Round Table Agreement were:

(1) Solidarity was to be re-legalized;

(2) strikes were to be legal and people punished for strikes in the past were to be compensated;

(3) the Judiciary was to be independent;

(4) the economy was to be based on the free market, but wages were to be indexed up to 80% of price hikes (This was forced through by Alfred Miodowicz, leader of the official Trade Union).

(5) the Senate (abolished by the Communists in 1947) was to be re-established with 100 members as the upper house, though the Lower House (Sejm, pron. Seym) with 460 members, was to have legislative power.

(6) Elections were to be held in May or June - but 65% of the seats in the Lower House were reserved for the United Polish Workers’ Party and its two satellites: the Democratic and Peasant Parties. Thus, only 35% of the seats could be contested freely in elections for the Lower House.

(7) the ministries of the Interior, Foreign Affairs, and Defense were to be in communist hands.

(8) the President was to have absolute power in these matters. He could also impose a state of emergency (martial law).

(9) The President, to be elected by the lower house for 6 years - was clearly to be Jaruzelski.

It should be noted that Jaruzelski and his supporters, known as "Reform Communists," had to fight hardliners within the party, but they had the support of Gorbachev.

Later, Solidarity leaders were criticized for some of these

agreements, notably the restricted elections to the Sejm. They replied that

they then feared failure to reach agreement would put the hardliners in power,

who would crush all attempts at meaningful reform.

Signing final documents in the sub-committee for political reforms

[from: Marody, Dlugi Final].

Signing final documents in sub-committee on Trade Union pluralism.

[From: Marody, Dlugi Final].

Former enemies sit down together: from left to right: T.Mazowiecki,

Cz. Kiszczak, L.Walesa, W.Jaruzelski, B.Geremek, M.Rakowski, Bishop T. Goclawski

- organizational meeting to set up a liaison commission.

[From: Marody, Dlugi Final].

It is clear the communists expected to win the elections because

they had the organization, control of the media, and money. Indeed, the PUWP

borrowed several million dollars from the Soviet Communist Party for the elections

campaign. Also, it was agreed that candidates were not to list party affiliations.

However, each Solidarity candidate had his picture taken with Walesa

and these pictures were plastered on walls all over the country.

The "Walesa Team."

[From:Sergiusz Kowalski, Narodziny III Rzeczypospolitej (The Birth of the Third Republic),Warsaw, 1996].

The Communists lost the election held on June 4, 1989. Polish voters crossed off on the ballots the names of almost all known communist candidates. This was a crushing and public defeat for the communists. (It was, however, overshadowed in the world media by the Chinese government’s massacre of students in Beijing on the night of June 3-4).

However, Walesa kept to the agreement that run-off elections be held and some communist leaders were elected. After this, two communist Premiers tried and failed to form a new government. Therefore, Jaruzelski asked Walesa to propose three names for the post of Premier - he did so, and the choice fell on Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a well known Solidarity journalist. Mazowiecki formed the first majority non-Communist govternment in E.Europe on Sept. 12, 1989.

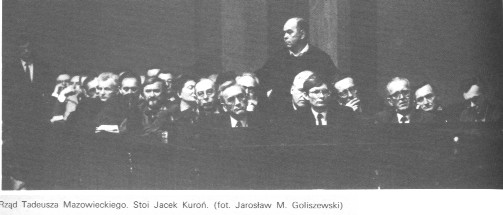

The Mazowiecki government; standing: Jacek Kuron.

The Statue of Feliks Dzierzynski is removed.

From: Kowalski, Narodziny III Rzeczypospolitej, 1995

(Dzierzynski, a Polish communist, was the first head of the Soviet Security Police, the Cheka).

Jaruzelski was elected President by the Sejm for 6 years - but with only l vote to spare. (He resigned in summer 1990, and Walesa was elected President by popular vote in Dec 1990).*

*[See R.J. Brown, The Surge to Freedom, ch.3, also Gale Stokes, The Walls Come Tumbling Down. The Collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe, (Oxford, 1993), ch.4, and same, ed, From Stalinism to Pluralism. A Documentary History of Eastern Europe since 1945, 2nd edition, (Oxford,1996), pp. 224-231; For an economic study, see: Bartlomiej Kaminski, The Collapse of State Socialism. The Case of Poland, (Princeton, N.J., 1991)]

2. Hungary.

Here, as in Poland, "reform communists" led by Imre Pozsgay - who seems to have enjoyed Gorbachev’s support - maneuvered for power. As noted earlier, Janos Kadar resigned as lst Secretary in summer 1988 to be succeeded by Karoly Grosz, and hundreds of Hungarian discussion clubs as well a political groups came into existence beginning with the fall of 1988.

Pozsgay as well as the anti-communist opposition, were encouraged by public declarations from Moscow that the USSR would not intervene in Hungarian internal affairs. The leading opposition group was the Alliance of Young Democrats, and it was tolerated by the government. Indeed, the ruling party, the HSWP, declared in January1989, that it was committed to a return to political pluralism.

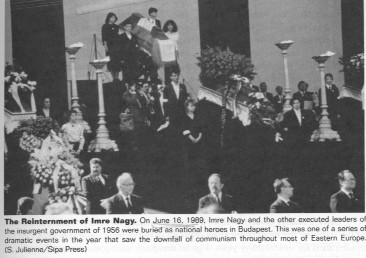

After the HSWP had rehabilitated the 1956 revolution, came the reburial of Imre Nagy and those of his collaborators, who had been executed with him and buried in unmarked graves. This occurred on June 16 1989 and marked the official rehabilitation of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.* Janos Kadar died three weeks later.

from: Lyman H. Legters, Eastern Europe.Transformation and Revolution, 1945-1991, Lexington, Mass, Toronto, 1992.

*[see Timothy Garton Ash, "The Last Funeral," The Magic Lantern, New York, 1990, pp. 47-60, reprinted in Lyman H. Legters, ed., Eastern Europe. Transformation and Revolution, 1945-1991, (Lexington, Mass.,Toronto, 1992), pp.435-443].

In July 1989, President George H.W. Bush visited Hungary - after Poland - and insisted on meeting publicly with the opposition party leaders. This influenced further developments in Hungary.

In September 1989, a group of Hungarian opposition parties, called the " National Roundtable," which had negotiated with the authorities in the period June-September, reached a series of agreements with the ruling party on September 18, including the election of President by the Legislature and free elections the following year. However, some parties led by the Alliance of Free Democrats did not accept the agreement, insisting that the President be elected by popular vote, and not by the legislature. (This was to exclude the election of Pozsgay and was agreed on later). A referendum was held and the results supported a popular election of the president.

A new government emerged headed by Premier Josef Antal, a former High School teacher, medical historian, and leader of the Hungarian Democratic Forum party. On October 18th, the Hungarian parliament changed the name of the Hungarian state from the Hungarian People’s Republic to the Hungarian Republic, and restored the old Hungarian flag. On Oct. 23rd, thirty-three years to the day after the outbreak of the revolution of 1956, the Hungarian Republic was officially proclaimed from the balcony of the parliament building.

Rudolf Tokes has listed 5 key factors in the success of the Hungarian "negotiated revolution, which can be paraphrased as follows:

(1) The Polish Roundtable Agreement of April 6, 1989 -- without which K. Grosz would have hesitated to embark on a similar process in Hungary;

(2) Aleksander Yakovlev’s meddling in the rivalry between Grosz, Nyers, and Pozsgay in spring-summer 1989 made Grosz’s survival against the reformers impossible. (Yakovlev was a key adviser to Mikhail S. Gorbachev and carried out his policy of supporting the reform communists);

(3) Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu’s criticism of Hungarian "nationalist" tendencies and his oppression of Hungarians in Romania, helped the Hungarian Democratic Forum win the by-elections in summer 1989;

(4) Gorbachev consented to Hungary opening the iron curtain by tearing down the barbed wire on the Hungarian frontier with Austria in September 1989, thus allowing thousands of East Germans - who were in Hungary as tourists -to travel from Hungary to Austria, then on to West Germany;

(5) President George H.W. Bush’s insistence on meeting with opposition party leaders in July, eliminated the temptation for Grosz and his supporters to end their dialog with the "insurgents" (opposition) in that same month.*

*[For a detailed account of Hungarian events in 1989, see: R. Tokes, Hungary’s Negotiated Revolution, ch.7; the text of the Sept. 18, 1989 agreement is in appendix 7.1, pp. 356-360. See also J.F. Brown, Surge to Freedom, ch. 4, and Alfred Reisch, "Hungary in 1989: A Country in Transition," in Legters, Eastern Europe, pp. 443-449.]

3.The collapse of the German Democratic Republic.

As mentioned above, in the fall of 1989, the Hungarian government allowed thousands of East German tourists to proceed from Hungary to Austria, whence they traveled to West Germany. Those who were in Czechoslovakia were allowed to cross part of the GDR in sealed trains, so other East Germans could not come aboard.

This exodus began in September, when Hungarian border guards took down the barbed wire along the Hungarian-Austrian frontier, and the previous erratic flow of East Germans to Austria became a flood. It is estimated that some 120,000 East Germans reached West Germany in this way.

In early October, Gorbachev visited the GDR on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of its establishment (Oct. 7, 1949). He made it clear to the East German leader, Erich Honecker, that change was necessary, also that Soviet troops in E.Germany (about 400,000) would not intervene to support the government. He publicly spoke of the need for change and was cheered enthusiastically by the crowds, as the GDR party leaders looked on.

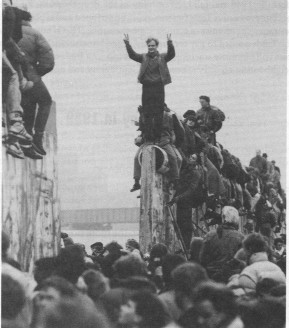

Gorbachev’s statements sparked pro-democracy demonstrations all over the GDR, but especially in Leipzig and Dresden. The German police beat up demonstrators and it is known that a bloodbath was averted in Leipzig by the intervention of some local communist leaders. Tension grew until Honecker resigned on October 18 to be succeeded by a new leader, Egon Krentz, who opened passages in the Berlin wall on November 9. This was the result of a careless statement by another party leader, Gunther Schabowsky, who was asked when people could go to West Berlin, and said: "right now." Thus, the wall came down on Nov. 9, 1989, and masses of people demonstrated for a united Germany.

The opening of the BerlinWall, November 9, 1989.

*[See: J.F.Brown, Surge to Freedom, ch. 5].

4. The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia.

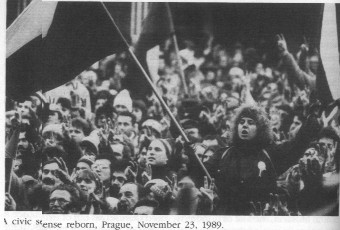

The events in Poland, Hungary, and Germany were followed by the Czechs on Austrian or German TV On November 17, a student demonstration was crushed by police in Prague. However, when news came that a student had been killed (it turned out later that he was wounded), masses of people came out in protest and were soon joined by the workers.

On November 19, a committee came into being

under the leadership of Vaclav Havel. It was made up of members

of Charter 77 and moved from one theater to another called the Magic

Lantern Theater. They constituted an umbrella organization called the

Civic Forum, drew up demands, and soon gained the support of the

workers.

All were encouraged by Premier Ladislav Adamec’s declaration that there

would be no imposition of martial law. Alexander Dubcek arrived in Prague

on November 24th, and supported the Civic Forum. Demonstrations continued and

the workers threatened a general strike. Similar demonstrations took place in

Slovakia.

The communists tried to mobilize support, but the communist National Assembly passed a resolution to delete from the constitution the article proclaiming the leading role of the Czechoslovak party.

from: The Velvet Revolution, 1992.

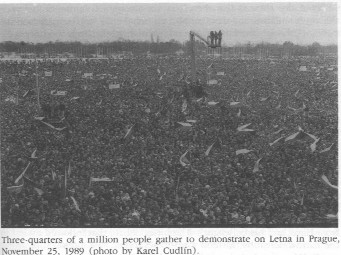

On Nov. 26, the Civic Forum members met with Premier Adamec, who proposed a coalition government of 21 members, of which 16 would be communists. This was rejected by the Civic Forum. On December 4th a huge demonstration called for a general strike on the. 11th if the govt. did not resign, but it did.

from: Wheaton & Kavan, The Velvet Revolution, 1992.

President Gustav Husak swore in a new government. on December 19th. It was made up of former dissidents and included Petr Miller for the workers. On December 28th, the National Assembly elected Dubcek as chairman (speaker) and next day, it elected Havel as President. Thus, the so-called Velvet Revolution (no violence) overthrew communist rule in Czechoslovakia.

Havel analyzed the past and outlined the goal of the revolution in his New Year’s Day speech, January 9, 1990. It is worth citing some of his statements because they exemplify his humane and balanced views, and they in turn, exemplify the best features of the Czechoslovak political tradition. Havel said:

All of us are responsible, each to a different degree, for keeping the totalitarian machine running. None of us is merely a victim of it, because all of us helped create it together...The recent times, especially the last six weeks of our peaceful revolution, have shown what an enormous generally humane, moral, and spiritual charge and what high standards of civic maturity lay dormant in our society under the mask of apathy that had been forced upon it...Of course, for our freedom today we also had to pay a price. Many of our people died in prison in the 1950s, many were executed, thousands of human lives were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of talented people were driven abroad...Neither should we forget that other nations paid an even higher price for their freedom today, and thus they also paid indirectly for us too. The rivers of blood which flowed in Hungary, Poland, Germany, and recently too in such a horrific way in Romania, as well as the sea of blood shed by the nations of the Soviet Union, should not be forgotten, primarily because human suffering affects every human being. But more than that, they should not be forgotten because it was these great sacrifices which wove the tragic backcloth for today’s freedom or gradual liberalization of the nations of the Soviet bloc, and the backcloth of our newly charged freedom too. Without the changes in the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary, and the German Democratic Republic, the developments in our country could hardly have happened, and if they had happened, they surely would not have had such a wonderful peaceful character.....

Masaryk founded his politics on morality. Let us try, in a new time and in a new way, to revive this concept of politics...

Our worst enemy today is our own bad qualities - indifference to public affairs, conceit, ambition, selfishness, the pursuit of personal advancement, and rivalry -- and that is the main struggle we are faced with...

Perhaps you are asking what kind of republic I have in mind. My reply is this: a republic that is independent, free, and democratic, with a prospering economy and also socially just – in short, a republic of the people that serves the people, and is therefore entitled to hope that the people will serve it too....

People, your government has returned to you!.. *

The Gorbachev Factor

It is clear that in Czechoslovakia, as in Poland, Hungary, and East Germany, communism fell not only because people wanted to get rid of it, but also because Soviet leader Mikhail S.Gorbachev supported change and opposed the use of force to stop it. We do not know his thoughts on these events at the time,* but we can assume that he expected the Polish Roundtable Agreements would work, that is, the communists would hold the levers of power while liberalizing the system, thus making it more popular.

When it turned out that this would not work, he decided to accept the fall of communism. He did so probably because using Soviet force to prop it up would have destroyed the good relations he had established with the United States and thus risk renewing the Cold War. Whatever his motives, the world owes a great deal to this Russian statesman. **

*[Gorbachev does not say anything about his thoughts on E. Europe in 1989 in his Memoirs, published in English translation in New York, 1996. He only speaks about Soviet relations with Socialist countries at the beginning of his tenure as lst Secretary.

**Karen Dawisha was probably close to guessing Gorbachev's thinking

when she wrote: "Gorbachev may turn out to be a ’Westernizer’ prepared to allow

the democratization and liberalization of Eastern Europe within the continued

framework of communist rule."See: Karen Dawisha, Eastern Europe, Gorbachev

and Reform. The Great Challenge, (Cambridge, England, 1988), p. 214. The

book was probably finished sometime in late 1987 or early 1988].

II.The collapse of Communism in the Balkans.

It is likely that Gorbachev’s ideas for liberalizing Eastern European communist states worked out best in the Balkan states of Bulgaria and Romania.

1. Bulgaria.

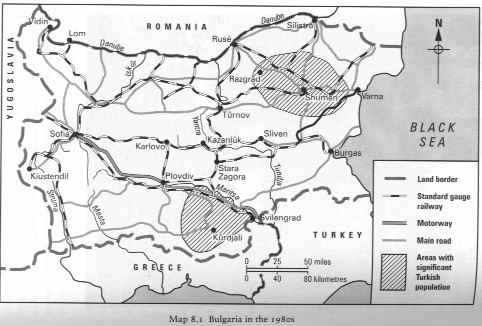

There was no dissident movement in Bulgaria, but small groups in defense of Human Rights and in support of Perestroika and Glasnost were crushed in 1988-89 by Todor Zhivkov who headed the party since 1954.

The same fate befell small groups such as the Trade Union organization Podkrepa (Support), and the "Committee for Religious Rights, Freedom of Conscience and Spiritual Values." The ecological protest group, "Econoglasnost," fared somewhat better.

Most importantly, some reform communists were ready to

take over power. They were led by Prime Minister Georgi Atanasov, Foreign

Minister Petar Mladenov, and Minister of Foreign Economic Relations Andrei

Lukanov, whose family had been repressed by Zhivkov.

The turning point for them was apparently Zhivkov’s decision in May 1989, to

get popular support by playing on Bulgarian nationalism. He had been following

a policy of forced assimilation toward the Turkish minority, which amounted

to about 10% of the total population. Now, he expelled Turkish minority

leaders and then allowed a massive exodus of some 350,000 Bulgarian Turks

to Turkey. This not only deprived Bulgaria of many valuable workers, but

also outraged western opinion.

from: R.J.Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, Cambridge, England, 1997.

When change came, it looked like a planned coup. Zhivkov was forced to resign on Nov. 10, 1989, one day after the Berlin Wall was breached.

Three days later, he was replaced as President by Mladenov,who had just returned from Moscow. However, a new opposition group named the Union of Democratic Forces, published a 10 point reform program similar to those of E.Germany and Czechoslovakia, that is, free elections, the rule of law, a free and independent press, free trade unions and a multiparty political system. After a December 10 pro-democracy demonstration in Sofia, Mladenov promised the abolish the Communist party’s monopoly of power and hold free elections in spring 1990.*

*[See: R.J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, pp.205-215; J.F. Brown, Surge to Freedom, ch. 7; John D. Bell "Postcommunist Bulgaria," deals with the Zhivkov period and the revolution of 1989, see Legters, Eastern Europe, pp.488-492 ]

2. Romania.

Nicolae Ceausescu’s corrupt and cruel dictatorship has been described earlier (see Lec. Notes 18B). Let us recall that he not only paid off Romania’s foreign debt by drastically lowering the people’s standard of living, but also prohibited abortions in order to increase the birthrate. This resulted in large numbers of unwanted children housed in dreadful conditions in state orphanages, where many infants were given blood transfusions to strengthen them. Unfortunately, some of this blood was infected with HIV.

He also destroyed many historic buildings in Bucharest to make space for a huge "Palace of the Peoples" - really a palace for himself. Furthermore, he destroyed many old villages, mostly Hungarian, in Transylvania. He forced these farmers into concrete, three-storey buildings without running water or elevators.

His wife Elena and their son Nicu, both of whom held powerful state positions, were hated almost as much as he was.

Under Ceausescu’s terror, there was little scope for dissent. The intellectuals were generally compliant, though some courageous individuals risked their lives to voice opposition. Here special mention shoud be made of Doina Cornea, a language teacher in Cluj, the writer Ana Blandiana, and the poet of the revolution: Mircea Dinescu.

The Orthodox Church cooperated with the regime, but here too there were exceptions like Father Gheorghe Calciu, a long time opponent of Ceausescu’s policies.*

The most outspoken protest by an intellectual was written by a Social Sciences professor at the University of Bucharest, Silviu Brucan. His open letter, addressed to President Ceausescu, was signed by five other dissidents, all of them party members, and is known as "The Letter of the Six." It was put in a mailbox at the Intercontinental Hotel, Bucharest, on February 27, 1989, and copies were sent to various addresses in Western Europe. It was broadcast by the Romanian service of the British Broadcasting Corporation, as well as other western Romanian-language stations and published in major international newspapers on March 19-12, 1989. The letter enumerated Ceausescu's crimes:

(1) It protested against Ceausescu’s violations of the Helsinki

Final Act of 1975 (human rights, which Romania had signed);

(2) his violation of civic rights guaranteed by the Romanian Constitution.

(3) the "modernization plan" for villages, that is, their destruction and forcibly

moving the inhabitants to concrete apartment blocks;

(4) the costly construction of the "Civic Center" in Bucharest (the Palace of

the People);

(5) the persecution of the people by the Securitate (security police);

(6) forcing workers to work on Sundays;

(7) the violation of privacy in the mail and telephones;

(8)the failure of economic plans; the chaos in agriculture, with resulting food

shortages;

(9) the forced assimilation policy followed towards Germans, Hungarians and

Jews, which resulted in emigration;

(10) the deterioration of Romania’s international position.

To stop this negative process, the letter proposed that Ceausescu start by taking three steps:

(1) stop the policy of "systematizing" (modernizing) the villages;

(2) restore the constitutional guarantees of civic rights;

(3) end the food exports that threatened the "biological existence of the nation."

The signatories of the letter were: Gheorghe Apostol, former Politburo member and chairman of Trade Unions; Alexandru Barladeanu, former Politburo member and chairman of the Planning Committee; Corneliu Manescu, former Minister of Foreign Affairs and President of the U.N. General Assembly; Constantin Parvulescu, a founding member of the Communist Party; Grigore Raceanu, a Communist Party veteran; and Silviu Brucan, former acting editor of Scinteia. (The leading party paper. He was Romanian Ambassador to Washington in 1956-59, and to the U.N. in 1959-62).

The letter did not lead to the overthrow of Ceausescu, but it alerted the world to the situation in Romania and was a courageous step taken by Romanian intellectuals against the regime. They were all arrested. Brucan was released on December 22, just in time to take part in the revolution.

Finally, it should be noted that the workers themselves had protested against economic privations. Some went on strike in a large factory in Iasi, in February 1987, followed by students at the university there. Other workers protested in November, in Brasov, the second largest city in Romania, demanding food and freedom. They were crushed and subjected to a reign of terror, but their protests prepared the way for the outbreak in Timisoara in late 1989.

Given all these factors and circumstances, it is not surprising

that the collapse of communism in Romania turned out to be bloody affair. On

December16, 1989, there was unrest in the town of Timisoara,Transylvania,

which centered on a police attempt to arrest a popular dissident Pastor of the

Hungarian Reformed Church, Laszlo Tokes. This led to a confrontation

with the security police.

The "Timisoara Revolution" lasted until December 20, when it claimed victory.

It was certainly an anti-communist revolution.

Someone spread the rumor that there were hundreds and even thousands of deaths - though the real number was very small -- and this outraged people all over the country. When Nicolae Ceausescu returned from a state visit to Iran, he appeared on December 21st with his wifeElena on the balcony of the Palace of the Peoples in Bucharest and made a speech condemning the rebels of Timisoara as agents of foreign intervention. But the usual organized applause was drowned out by student whistles (a sign of disapproval), cat calls, and shouts that Ceausescu was a tyrant. He looked shocked and frightened, and the state TV went off the air. Nicolae and his wife Elena fled in a helicopter.

Fighting broke out in Bucharest between the people, joined by the army on the one hand, and the Securitate, the infamous Romanian security police, on the other. Soon a group of revolutionaries and former communist opponents of the regime took over state TV and declared the fall of Ceausescu.

Meanwhile,the Ceausescus found they could not use the airport because it was in rebel hands, so they commandeered a car and drove to the town of Tirgoviste. There, they were taken into custody by the commander of the local army garrison who hid them for three days in a room in the barracks, so they could not be rescued by the Securitate.

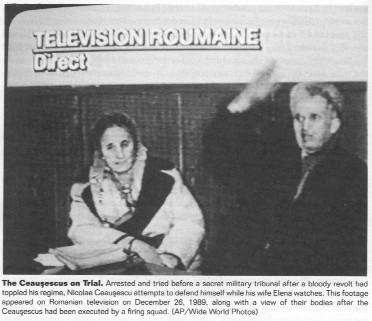

A general came down from Bucharest and ordered the trial of Nicolae and Elena on charges that included genocide against the Romanian people. (Ceausescu was, indeed, responsible for many deaths, but he was not guilty of genocide).

A kangaroo court was set up in the army building. Ceausescu demanded a trial by the National Assembly, to which he was entitled as President, but this was refused, for as long as he lived, the Securitate was expected to resist. He rejected his defense lawyers’ advice to plead insanity.

On December 25, Nicolae Ceausescu was condemned to death along with Elena, and both were shot by soldiers in the garrison H.Q. courtyard. Their bodies were shown on Romanian TV to end Securitate resistance.

from: Legters, Eastern Europe.

The "reform communists," led by Ion Iliescu, formed the "National Salvation Front" in December 1989 and held on to power until 1996. This government of "post-communists" was opposed by the revolutionaries who saw it as a betrayal of the revolution.*

*[see J.F. Brown, Surge to Freedom, ch. 8; for the account of a high-level participant, see: Silviu Brucan, The Wasted Generation. Memoirs of a Romanian Journey from Capitalism to Socialism and Back, Boulder, CO., 1993, ch. 10, "The Inside Story of the Revolution." for the text of the "Letter of the Six," see pp. 155-157; for the Timisoara Declaration of March 11, 1989, see: Legetrs, Eastern Europe, pp. 473-479.].

3.Yugoslavia is a different case from other E. European countries, for like the USSR, its disintegration was primarily due to ethnic/national rivalries and enmities, accompanied by a desire for democracy. This process, though begun in 1987, really belongs to the post-1989 period. [See Lec.Notes 20].

4.Albania.

The last country to overthrow communist rule was Albania,

which did so in 1990 Its story also belongs to the post 1989 period.

[Lec.Notes 20]

************************

.